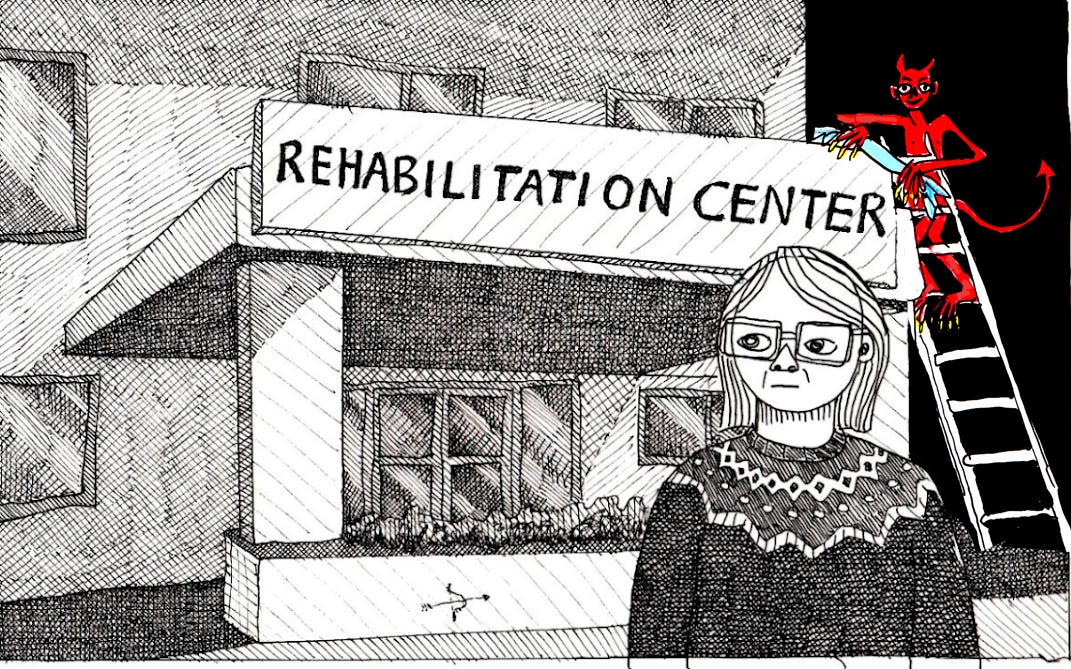

What It’s Like to Go to Rehab

The first day of the rest of your life.

If our newsletter has helped you feel less wicked and alone, less shitty or afraid, then please consider financially supporting us. Subscribers gain access to the entire archive, the Sunday essay, the complete recommendations roundup, and the comprehensive rundown of my weekly recovery program.

If you’d like to become a paid subscriber but can’t afford it at this time, email me: ajd@thesmallbow.com and I’ll hook you up.

Clear eyes, full hearts, etc. —AJD

Ten years ago this week, I went to a West Palm Beach-ish, Florida treatment center called HARP for almost two months, after a summer spent quick-sanding deeper and deeper into drugs, alcohol, plus several manic episodes, depressive anger, and all that other chaos that overtakes a life fueled by All The Things.

I can safely share that I don’t believe I ever would have stopped had I not landed in treatment. I’d made attempts to quit before — a few weeks here, six days there. I even did a 9-day stay in a North Jersey detox in August that didn’t stick. And I wish I had stayed longer, just to gain even more separation from my old life, the tattered one that was waiting for me back in New York, because I needed that structure. But it’s not for everyone — and it’s expensive. I was lucky to have some great insurance that covered most of my stay, but spending upwards of $30k a month to get healthy is not feasible for most people. And I didn’t go to a super-fancy rehab — it was billed as “holistic,” but it was your standard South Florida facility with borderline contemptible business practices and not a very high success rate. I’ve had several people reach out to me and ask about rehab — would it work for them, is it scary, all that. I can tell them about my experience, but what they need is many more experiences. And that’s the goal of this month’s “What It’s Like . . .” feature: What was it like to go to rehab? Was it a good experience? How many times did you go? Tell us your story.

All contributors will remain extremely anonymous.

Please keep contributions to under 500 words.

Send your stories here: tsbcheckins@thesmallbow.com

Subject: REHAB STORY

Anyone who submits gets three free months of TSB Sundays.

And below, I’m re-running an old essay that spoke at length about some of my experiences, followed by one of my favorite October-tinged rehab-y poems. Thanks for helping us out. —AJD

*****

The End

of the Beginning

of The End

by A.J. Daulerio

******

Originally published October 20, 2021

*****

On Saturday, October 17, 2015, I took a selfie just a few minutes before my US Airways flight departed JFK for West Palm Beach International Airport (PBI), arriving at approximately 9:50 a.m. This was the third flight I’d booked to PBI in 36 hours. I missed the first two. I wanted to “push the date” as I frequently did then, not because I was busy, but because I was selfish and irresponsible.

This time, it wasn’t an important meeting I was bailing on, a doctor’s appointment, or a work deadline, but drug and alcohol rehab, my second attempt in two months to get institutionally sober. Eventually, I wanted to go and knew I needed to go, but I didn’t want to go just yet.

I took a selfie right before takeoff. I’m wearing a black hoodie and a dour expression, and I’m giving the finger, but I completely forget why. The photo was evidence that, yes, I finally got on the damn plane. Here I am! It was time.

It was a half-empty flight, with an eerie lack of turbulence, even on takeoff. It was as if the plane just floated the whole way there. I sat in the middle row. I had that paper pillow behind my neck, but didn’t sleep. I had a tin of Kodiak, but I didn’t need it. I usually bought some because I couldn’t fly for more than two hours without nicotine for most of my adult life. I used to buy a Snapple at the airport, chug it all before takeoff, and then spit in the bottle throughout the flight. I’d get up once or twice to dump the sloppy brown dip spit from the bottle into that noisy toilet. Sometimes, the tobacco hunks stuck to the insides of the bowl. I would reach in with one of those cheap paper towels and scoop it out because I didn’t want the next person to think I was a scumbag, even if I was.

No dip on this flight, though. That felt like a huge first step away from the darkness and into whatever light awaits after I return. I drank two cans of “Mr and Mrs T’s” Bloody Mary mix without any vodka. I stared at the can and realized there were no periods after the ‘r’ and the ‘s.’ Without any vodka, you notice things like that.

As the plane descended, the pilot announced that the temperature in West Palm Beach was about 77 degrees. “Welcome home to those who call this home. I hope everyone else enjoys their vacation. It’s gonna be a perfect weekend in South Florida.”

I could make this a vacation, I thought. I could push the date on this rehab stint one more time. I should enjoy this perfect weather. A few days in the sun could be all I need to straighten out. What if, instead of rehab, I took a cab to some hotel and went out that night for crabs and beers like a Normal Person?

But the idea that I would disappoint people again—I can’t. Then I got really cold. I felt that kind of cold once when I had some minor heart surgery to repair a troublesome tachycardia. I’d been operated on before, but that time, for whatever reason—the scratchy gown, harsh lighting, some rando intern using a plastic disposable razor to shave my groin area—I began to shake. I shook like my dog used to when we took her to the vet. “He’s got the shivers,” one nurse told another nurse. “Can we give him something for the shivers?”

When I left my gate, a caramel-sunburnt man of about 60 named Bud was waiting for me. He held a sign with my last name misspelled. He was there to drive me to the detox center a few miles away from the center in Lake Worth. On the way there, he talked about how he was retired and volunteered for this gig because his ex-wife was “one of you guys.” He said being a rehab taxi has made it easier to forgive her for the hell she had put him through. He let me smoke in the car the whole way there, so it was a nice ride.

This was a much better start than the last time I’d gotten a ride to detox two months prior. I can’t remember what that driver’s face looked like. I’d waited nearly five hours for him to pick me up, and I was pretty wasted by the time he pulled up in front of my Williamsburg apartment.

For what felt like dozens of hours, he drove to a gray part of North Jersey surrounded by spooky farmland and sandwich shops. The facility was called Sunrise or Sunbeam or Sunshower — some sort of regenerative Sun. I arrived there late at night, full of Xanax and blow, and once I was all checked in, my good insurance allowed me to choose between a room with a twin bed and a roommate or a private room with a queen bed. Easy choice.

I was given Librium and Trazodone and told to grab something from the kitchen if I was hungry. They had a fridge drawer full of those Uncrustables peanut butter and jelly sandwiches that were so cold and perfect. It was one of the greatest meals of my life.

I avoided most people and kept my routine tight: Wake up. Smoke. Eat. Smoke. Half-hearted pushups in my room. Smoke. Pretend to sleep.

Everyone there was so young, but many had gone to detoxes like this two, three, half a dozen times, from Jersey to Florida to Arizona. One kid attempted to make small talk with me about my drug of choice (“What’s your DOC?”) and asked me where I was from — the usual icebreakers of the lost — but I mumbled and cut him off because he had a giant bubbly abscess the size of a cockroach on his right hand. Whatever I mumbled was probably not what I wanted to say, what everyone wanted to say: “I’m not supposed to be here.”

One of the Sun-something technicians (that’s what they call the non-medical staff there) was an arrogant 30-something dude who strutted around like a lifeguard, but instead of twirling a whistle, he carried a giant vaping device about the size of a wizard’s scepter. He ran group therapy one day and tried to browbeat us all into sobriety. “Does everyone here want to be a loser their whole life?” No one answered.

The first couple of nights in my private room, this same technician woke me up to take my vitals every hour, and he’d always remind me not to isolate. “Don’t isolate, bro.” Every time. “Don’t isolate, bro.” But that’s exactly what I did because that’s all I wanted to do. I left after nine days.

*****

When I got dropped off at the Lake Worth detox, it, too, was called Sunrise Detox Center. I didn’t have any drugs or alcohol in my system this time around, which meant I only had to stay there a couple of days, and I would get the first available bed at the rehab. I was given Trazodone but no Librium.

There was a couple who checked in together the same day I did. They couldn’t have been more than 30, with shirts so big on their skinny bodies that it looked like they were wearing hockey jerseys. You could tell they’d been up for several days but were totally in love. They were always in each other’s laps, making out next to a sand-filled ashtray like they were at a beach house after prom.

I had to share a room and slept on a small single bed with a plastic fitted sheet. The other guy in my room was thrown out within the first couple hours I was there for sneaking in oxy. He caused a whole scene and accused the staff of stealing his money and sweatshirt.

There was another fridge full of Uncrustables, but I didn’t touch them. One of the technicians there told me David Cassidy from the Partridge Family had recently stayed for two weeks. He died two years after that from liver and kidney failure due to his alcoholism, and his daughter said his last words were “So much wasted time.”

*****

A bed finally opened up. Bud The Driver returned to drive me from the detox center to the HARP rehab facility, a small, holistic-based program in Singer Island, Florida. Based on the website photos sent to me via email by the rehab broker I hired, HARP looked like many of the 55-and-over rental condos my parents looked at before they moved to nearby Jupiter.

Singer Island sounds fancy, but it’s more like an abandoned resort town, the kind of place that a developer in a ten-gallon hat had high hopes for until he ran out of money. And here’s some twisted geography: West Palm Beach is one of the easternmost cities in South Florida. Lunacy.

I wanted to try harder at HARP and punish myself for my many failed attempts to get sober. So I handed over my iPhone to one of the intake people, who put it in a locker. I even agreed to share a two-bedroom dorm with three other dudes in their 20s. It was pretty much what I expected. They always bummed cigarettes, pounded pre-workout drinks before breakfast, and wore shower shoes everywhere. They also gave each other haircuts with expensive clippers in the kitchen, so hair was all over the dishes. I was sure one of them would be dead in a year. They were all nice, though.

In early morning group therapy, the facility prided itself on integrating new clients as quickly as possible, sometimes on their first days. One of their methods was straight out of an EST orientation: Tell everyone three fun facts about yourself. Go.

“I have blue and brown eyes, I love plants, and I’m getting sued by Hulk Hogan for One Hundred and Fifteen Million Dollars” was what I came up with.

That didn’t land the way I thought it would. Another 22-year-old, who was not my roommate, looked at me strangely and asked if I was joking. He was annoyed, vaguely threatening. I wasn’t, but yeah, sure. Haha.

I was desperate to show I was smarter than them. I never got to be smarter than anyone back in New York. But I assumed I was Mensa material at this janky place in Abandoned Hobo Resort, Florida.

During one of the group spirituality sessions, the in-house therapist discussed David Foster Wallace’s commencement speech, “This Is Water,” and showed an artlessly remixed YouTube version titled “THIS IS WATER!” on a projection screen.

Afterward, I pulled the counselor aside — an incredibly kind and hope-filled woman named Laure n —and told her that it seemed odd and crass to show that here with so many desperate people. “Ya know, the guy who wrote that essay hung himself, right?” She nodded politely but exasperatedly, and then she asked me why it was so necessary to tell her that information. I had no answer.

I didn’t get lonely until Halloween. There was a silly, no-costume costume party in the common TV area, and everyone got to eat one piece of candy and drink one can of soda. Back in Brooklyn, I knew a huge house party was happening. There would be kegs and real costumes and mushrooms. If I hustled, I could catch a flight and be there before it ended. What if nobody wanted me there, though?

*****

Around early November, three weeks in, things clicked for me — I got good at rehab. I perfected a backward half-court shot that would knock people out in H-O-R-S-E. I knew the exact amount of time it took to make perfect microwave popcorn. I learned how to play spades. Beach volleyball ruled. Lauren, the counselor who was annoyed by me in week one, now treated me more like a peer than a patient. She told me I was very wise, and I believed her.

*****

I still have dreams about rehab, specifically, the vans that would drive us around. They would seat ten, sometimes 12 people, and it would either have the raucous energy of a party bus headed to a wedding or be silent and nervous like we were driving through a dense fog. Our vans took us to group therapy sessions in the morning and AA meetings at night. Sometimes, we went out for donuts and coffee if we were good. We went bowling once, and I felt transported back to a 5th-grade birthday party.

One very early Sunday morning, the van took me and two very young people who were skinny and washed out from heroin to church. I wasn’t converting or even searching; I just wanted to pretend I was participating in a normal Sunday ritual anyplace else on earth with other normal Sunday people.

Once, the van took us to a nearby shopping center where we were allowed to get supervised haircuts or pedicures. The pedicure option was primarily for this kid named Joe, whose toenails were so black with grime it looked as if a stampede of cattle had trampled his feet. He would always wear flip-flops, too. Nobody ever sat next to him in the van.

On the way back from the shopping center, a 20-something kid named Julius was in full lament about the James Bond film Spectre. “I hope it’s still in theaters when I get out of rehab.”

After he said that, I felt a real sense of loss. The idea that the 45-minute, very, very limited excursion was the highlight of my Saturday — and felt like a true luxury — reminded me that I was nowhere.

I wondered why I didn’t run away. We weren’t shackled. The technicians were not armed with batons or tasers. But if I did run, where would I go? We weren’t allowed to carry wallets or phones. I would be running away for another mile, probably to a Publix parking lot or another shopping center that would look exactly like the one I’d run from, just to return to the treatment center without anything to show for it. Here was my old life and new life, separated by the windows of this van, like the plexiglass between a prisoner and a tired family member who’d had enough.

But rehab changed me, just not how I thought it would. Once I got out and re-entered the world, I realized I knew less about myself than when I took that middle finger selfie.

I still have my rehab journal. It’s a crinkly old green Mead One Subject Wide Ruled Notebook. 70 sheets of paper. It has only one entry written in pencil on October 19, 2015. I wrote, “This is the part where you try to figure out how this all happened.” Then there are about 100 more words of halfway contrite nonsense, but my tone suggested I had already considered myself healed. And underneath that entry, also written by me in pencil, is a note with an upward arrow: “This guy sucks.”

*****

Your turn: tsbcheckins@thesmallbow.com

Subject: REHAB STORY

MORE IN THIS SERIES:

What It's Like to Have Money Shame

"I got a $35K bonus from work in 2023, and it all went to debt. I closed out the year having accumulated that exact amount of debt again."

What It’s Like to Be Addicted to P*rn

“Things I’d never said out loud — not even to myself — I shared with relative strangers, some of whom had just checked in that day. I went in there confident I would never talk about paying for sex with strippers, never talk about looking at animal porn, and sure as hell never describe how many times I’d been unfaithful to women.”

What It's Like to Use Ketamine! (For Your Depression.)

"I started to consider looking at Ketamine Assisted Psychotherapy in the summer of 2022. I am in long-term sobriety, connected with mutual support/12-step communities, and therapy. I was having a terrible, no-good time related to shame, depression, anxiety, and my general sense of self. I felt like I was doing the work and taking healthy actions, but I was beyond stuck."

*****

A POEM ON THE WAY OUT:

Zoloft

by Maggie Dietz

************************

Two weeks into the bottle of pills, I’d remember

exiting the one-hour lens grinder at Copley Square—

the same store that years later would be blown

back and blood-spattered by a backpack

bomb at the marathon. But this was back when

terror happened elsewhere. I walked out

wearing the standard Boston graduate student

wire-rims, my first-ever glasses, and saw little people

in office tower windows working late under fluorescent

lights. File cabinets with drawer seams blossomed

wire bins, and little hands answered little black

telephones, rested receivers on bloused shoulders—

real as the tiny flushing toilets, the paneled wainscotting

and armed candelabras I gasped at as a child in

the miniature room at the Art Institute in Chicago.

It was October and I could see the edges

of everything—where the branches had been a blur

of fire, now there were scalloped oak leaves, leathery

maple five-points plain as on the Canadian flag.

When the wind lifted the leaves the trees went pale,

then dark again, in waves. Exhaling manholes,

convenience store tiled with boxed cigarettes

and gum, the BPL’s forbidding fixtures lit

to their razor tips and Trinity’s windows holding

individual panes of glass between bent metal like

hosts in a monstrance. It was wonderful. It made me

horribly sad.

It was the same

years later with the pills. As I walked across

the field, the usual field, to the same river, I felt

a little burst of joy when the sun cleared a cloud.

It was fricking Christmas, and I was five years old!

I laughed out loud, picked up my pace: the sun

was shining on me, on the trees, on the whole

damn world. It was exhilarating. And sad,

that sham. Nothing had changed. Or

I had. But who wants to be that kind of happy?

The lenses, the doses. Nothing should be that easy.

*****