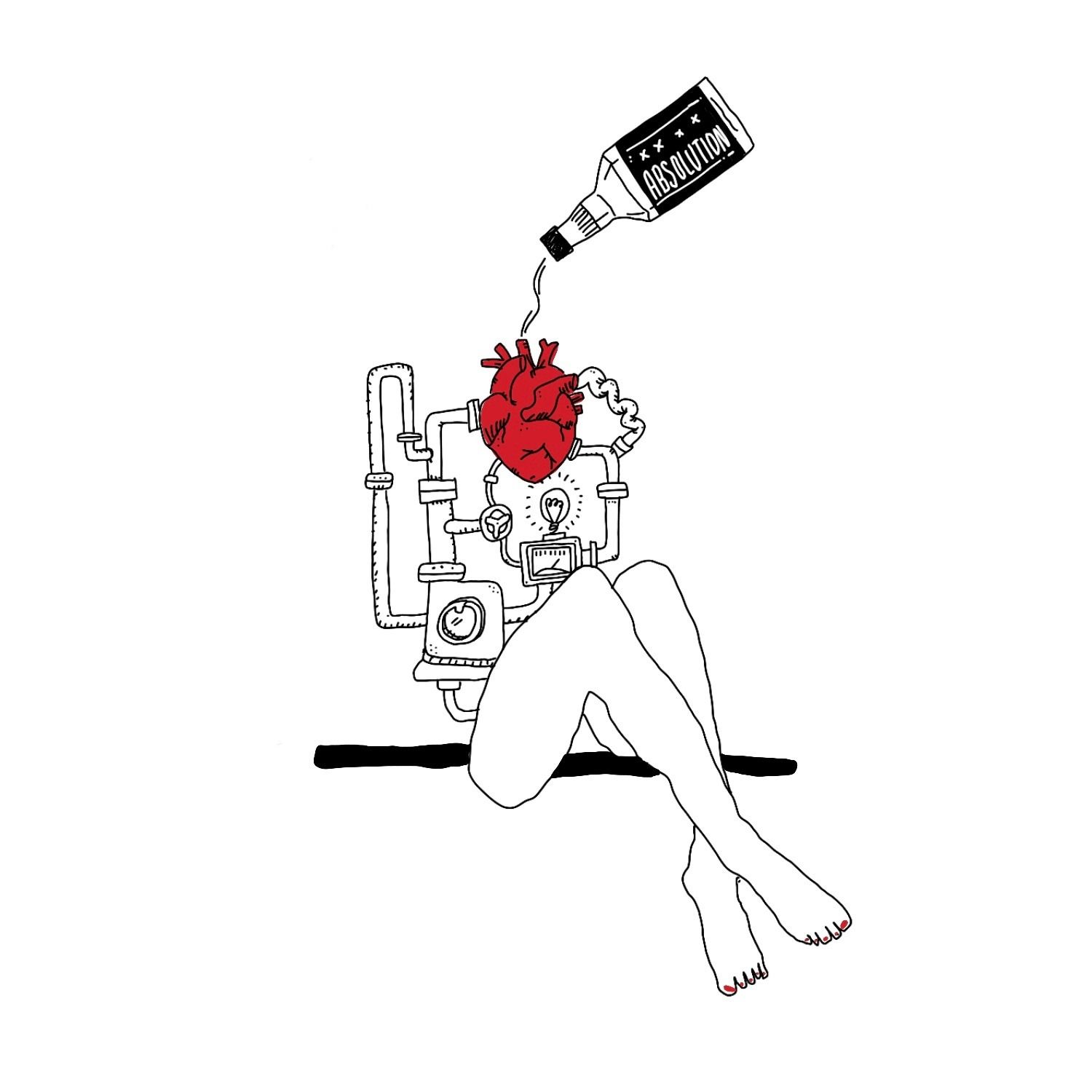

Today we have confessional essay from writer/illustrator Erin Williams about a topic that oftentimes goes overlooked when it comes to new-sobriety sex: How to feel . . . something.

Sex can’t be governed by that same law. “Never again” is sanity for alcohol, but not for desire. Sex must be learned and practiced so that ambiguity, choice, and risk can be handled safely rather than refused. Alcohol recovery demands refusal, but sexual recovery (if that’s even the right phrase) demands discernment. I am fluent in refusal. Discernment is a second language.

I discovered Erin’s writing about a month ago via this essay that ran on Memoir Land and thought her voice would work great here. This essay is long, so if you’re reading this in email I suggest viewing it on the page, since along with her words, Erin has also done her own drawings within the body of the essay. Her Substack is called “Is it Comics?” which began as “drawings but now spills into words: confessional essays about sobriety, midlife dating, and the messy human interior.” We highly encourage you to subscribe.

How to Have Confusing Sober Sex

by Erin Williams

I slept with someone new a few weeks ago. His politics (anarchy) were too extreme for me (a socialist). His face was handsome, his hair longer than I’d prefer, his arms sleeved with black-ink sigils that blurred into symbols I couldn’t quite read. We had a few dates that stretched for hours. He was sober too, and the intimacy that kind of mirroring creates was immediate, unguarded, oddly tender. I liked being with him. I couldn’t tell if I liked him in the way that moves a romantic story forward, or only in the way that makes time pass beautifully.

Our fourth date was at his apartment. Before I arrived, I wasn’t sure if I wanted to sleep with him (yet or at all), but I’d worn lace underwear just in case. He made me hot peppermint tea. We talked, held hands on his green velvet couch, and I nuzzled my face comfortably into his thin shoulders. He smelled sweet, his body warm. I hadn’t been held in months. I straddled his lap and kissed him. He led me into the bedroom. I followed.

I felt ambivalent about him, a mixed state I’ve learned, in my intellectual work, to treat as neither augury nor indictment, simply information difficult to parse in whatever present moment I’m in. But my body rarely proceeds at the pace of ideas, and even more rarely under their jurisdiction.

Before I got sober in AA, sex and drinking were the same technology. Both annihilated the mean girl in my head. Both promised short-term relief from self-consciousness. Both exacted a price that compounded into shame. I won’t romanticize the archive. Freedom there was indistinguishable from self-abandonment and (occasionally) from danger. The harm was real. I chased validation through sex with strangers, each night a new mirage that might save me from myself. I know intimately the post-sunrise walk home in a party dress, ripped stockings, hair smashed on one side and wild on the other, mascara in raccoon crescents, head splitting.

It was, in part, the shame of a drunken indiscretion that finally compelled me to end what had been my life’s most consistent relationship: my love affair with alcohol. I’d gleefully planned my boyfriend’s 30th birthday party. I left him and the party before midnight, absconding with another man.

I lied to him about where I’d gone, and I couldn’t face celebrating his 31st. I quit drinking and took him to see a movie. I was four days sober.

When I was 88 days sober, he proposed. Before my 8th month, we were married. Neither one of us had any idea who I was or would become in alcohol’s wake.

One of the things I became in the absence of alcohol was what my friends in Sex & Love Addicts Anonymous (SLAA) call “anorexic,” a term used to describe someone who avoids sexual or romantic nourishment. SLAA differs from AA in that abstinence isn’t possible; its members define sobriety not by renunciation but by discernment, since desire itself can’t be given up, only shaped into something survivable. (Though I may qualify, I’m not in SLAA, partly because its mirror of AA’s model risks extending sobriety’s life-or-death clarity into an arena where that clarity, for me, becomes distortion.)

Control was the principle; celibacy the strategy. Shame and trauma made touch feel like a test I was bound to fail. Most of my marriage lived inside the daily decision to avoid any kind of embodied vulnerability. On a cold Sunday afternoon, when a man on the subway followed me from car to car threatening to rape me, I went home and shaved my head. One less extension of myself to be grabbed. But it wasn’t only fear. It was a theory of self-preservation that felt like the only available method to keep from dissolving.

Within that marriage, I leaned hard on second-wave and #MeToo frameworks. I needed a way to name power, injury, and asymmetry. I needed to make sense of the present in the context of the past. I wrote a book about my victimization as a woman, and about my complicities. Those narratives helped enough to dull the bright ache of early-sobriety shame. They gave me structure to make sense of withdrawal, even as they flattened what wouldn’t fit.

There were plenty of ways to explain my lack of desire for my husband. Maybe it was because the foundation of our sex life had been during the worst of my drinking, and I associated it with the sharp ache of that era of my life. Maybe it’s because he wasn’t emotionally available, and we couldn’t connect. Ultimately, I don’t think he was compatible, sexually or otherwise, with who I became sober. I became myself. It isn’t his fault.

When my husband and I separated a couple of years ago, I wanted to know if I could want again. I began to date, and eventually to have sex. Some experiences were joyful and deeply pleasurable: some in love, some in passing, each a small astonishment. The surprise was simple and enormous. More was possible for me than I had permitted myself to imagine. Pleasure was possible. Whole-bodied, toe-curling, ecstatic, screaming, sober pleasure.

I pinned some of the encounters to the old scaffolding. The man who groped me, uninvited, in a Greenpoint doorway: harmful. The man who marched me to CVS for stain remover after I left a dot of blood on his sheets and made me watch him scrub: harmful. These labels are not wrong exactly, but they’re too final for what I actually lived. In the doorway’s immediate aftermath, I wasn’t sure whether I liked the roughness. Part of me did. I wanted the CVS man to be my boyfriend, even after the cleanup. He later rejected me. The narrative of harm arrived after the fact as a way to stabilize my disappointment and confusion.

Sex with the Anarchist was disappointing, which, in the immediate aftermath, I noticed myself instinctually classify as worthy of shame. While we lay in bed, I scanned for old reasons why I shouldn’t have allowed myself to sleep with someone I felt ambivalent about. But my antidote to shame had been, in part, claiming harm, even if abstract or systemic. In this case, I knew it didn’t quite fit. Between pleasure and harm, there was a field I hadn’t much considered.

I know how to distrust binaries when I’m writing or teaching. I know to question the comfort of clarity and the seductions of a clean answer. Yet when it’s my own body, my own nervous system registering a distant siren of uncertainty, the old circuitry lights up. I want to classify, evaluate, decide, and close the file.

AA, for me, has organized this reflex. Sobriety is the black-and-white game that keeps me alive: you drink, you die. The clarity isn’t an abstraction; it’s a guardrail. That moral simplicity is merciful when the stakes are death.

Sex can’t be governed by that same law. “Never again” is sanity for alcohol, but not for desire. Sex must be learned and practiced so that ambiguity, choice, and risk can be handled safely rather than refused. Alcohol recovery demands refusal, but sexual recovery (if that’s even the right phrase) demands discernment. I am fluent in refusal. Discernment is a second language.

In bed together with this actually lovely man, I couldn’t get out of my head and into my body. I wasn’t sure from moment to moment whether I was enjoying myself or not. I kept asking myself if I was doing something I didn’t want to do, or doing something wrong. I oscillated between pleasure and uncertainty. Should I stop or keep going? Not knowing felt like threat. Uncertainty itself became its own kind of heat, not pleasure exactly, but arousal’s anxious twin.

I am well rehearsed in situations like these, and typically dissociate. I watch myself from a distance, from somewhere outside myself, my body. My consent never wavered. What shifted was my clarity about wanting, not my capacity to choose.

Afterwards, I lay there, not assessing pleasure so much as meaning. I wanted a verdict. That’s the legacy of the twelve-step world: not simply to ask what happened, but to ask what it indicates about the state of my soul. It turns the continuous rough field of experience into something legible. The binary isn’t merely conceptual, it’s a survival tool that lowers noise and produces an answer, the kind of answer that keeps you from picking up a drink. But the same mechanism that keeps me sober also flattens nuance.

In every other facet of my life, I reject binary thinking. I can write convincingly about ambiguity as an ethical stance, about uncertainty as a form of attention. I believe those sentences. But I will not apply them to my drinking. And I struggle to inhabit them when I’m naked.

There is a small humiliation in discovering how little one’s ideas matter in the immediate vicinity of arousal and fear. The body, like any complex system, fragments old schemas but does not replace them wholesale. Knowledge adds a second layer rather than rewriting the first. Understanding does not overwrite instinct. It coexists with it in an uneasy overlay. The result is dissonance that feels, from the inside, like a failure of integrity. Like a place where shame might seep into the cracks.

“You are gorgeous,” he said without contraction after climbing off my body. I lay on my back and stared at the wall, away from his handsome face. I didn’t reply. My brain was sprinting. I wasn’t unsafe. I just couldn’t locate pleasure in the aftermath. I just hadn’t . . . liked it.

“Let’s get pizza,” I said. “I’m starving.”

I wanted the feeling to pass cleanly, to evaporate on its own. But I need more than the flux of feelings; I need an ontology. I want a vocabulary that neither abolishes harm nor sanctifies it, language that leaves space for difficulty without immediately converting difficulty into harm.

Inside, my self-talk still instinctively tries to police me into safety. Ambivalence about the Anarchist triggered classification: He’s wrong for me, or maybe I’m just wrong. The relief of self-contempt is familiar. But there is a critical difference between harmful sex and sex I don’t like. Harm is a boundary crossed or consent that is withdrawn or ignored. If consent remained intact and misfit is revealed in hindsight, I just wasn’t that into it. That distinction matters. It preserves accountability without pathologizing regret. The former requires repair or exit and the latter requires notice and adjustment. I am less experienced in situations I am sober enough to consent to.

There’s a critical contrast between these two moral economies. In one, uncertainty is a debt you must clear. In the other, uncertainty is the currency itself. The first makes you solvent by closing the account. The second asks you to remain in circulation. For alcohol, solvency is sanity. Erotic life resists such accounting.

The temptation I rarely name is to treat freedom like a reward, sobriety as a moral credit, and autonomy as the right to predict my own sensations. But freedom isn’t a title, it’s the capacity to remain with flux without freezing it into doctrine. That capacity is unevenly available (trauma reduces it and power distributes it), which doesn’t forbid experimentation so much as require responsibility for consequence. Consent is a minimum, not a pinnacle. For me that looks stupidly simple: Naming uncertainty out loud (“I’m not sure, can we slow down?”) and pausing when my attention leaves my body. I still struggle to slow down. Safety is a practice, not a verdict. Multilingualism is the aim. Many languages in one mouth. The sober brain minds the boundaries, the analytic mind keeps the questions, the body feels it all.

In practice, this multilingualism looks unheroic. It looks like postponing the verdict, letting an experience remain partial, allowing time to do some of the interpretive labor adrenaline or shame tries to quickly do alone. The morning after, my instinct towards shame crept up through the shower drain as logic tried to wash it down. My nervous system was trying to impose on the safety of the present moment the real and actual safety of the previous night. I feel gentler toward the impulse that wants the binary. It learned in high heat to make quick decisions. But I’m not always in that heat now. The protection that once saved me can, in this climate, obstruct possibility, pleasure, and perception.

The binary that keeps me sober doesn’t translate cleanly into desire. Sobriety taught me one language: survival. Sex, and everything that touches it, requires another. In that second language, the difference between harm and difficulty matters. They sound similar when spoken in fear, but mean different things. Difficulty isn’t danger. It’s dialect.

The work now is noticing when I start translating the world too literally, when I call uncertainty unsafe or mistake discomfort for damage. That’s an old tongue trying to speak in a new country. Differentiating fire from false alarm is a kind of linguistic fluency.

That night doesn’t need a verdict. Attraction and skepticism took turns; tenderness and analysis interrupted each other. It wasn’t harm, and it wasn’t revelation. It was just a moment of imperfect translation between my body and my mind.

Freedom isn’t certainty, but literacy. It’s the capacity to keep speaking through confusion without reverting to a single script. Not every misfire is trauma. Some are just mediocre sex. The point isn’t to be pure, but to stay conscious long enough to notice what’s real.

Some questions don’t need an answer. They just need to be asked, in every language I have, sober.

Erin Williams is a writer, illustrator, and teacher in New York. She writes about the hazards of dating and loving while sober. In 2019, she published her 5th step sex inventory as a graphic memoir. She wouldn’t necessarily recommend that approach.